I have figured out a way to improve humanity and possibly (probably?) broker world peace. Between the ages of 16 and 30, every individual should be required by law to work at least six months in a retail or food industry job. I will take my Pulitzer winnings in small bills and Amazon gift cards please.

Retail either forges or breaks you. It’s that simple. No one should have to withstand the humiliations suffered behind a counter or kiosk, should be expected to take the petty, often truly inane grievances seriously (“I’m sorry your child was traumatized because the Paw Patrol police vehicle siren was too loud. We’ll all take a moment to grieve their rejection from Harvard together. I can offer you store credit.”), yet this is where we find ourselves. Human to human, participating in debased interactions, conducting transactions with a level of profound absurdity that would make Kurt Vonnegut both terribly jealous and deeply depressed.

I don’t wonder why self-check kiosks are creeping up in numbers. People doing these jobs want a little peace and relief, maybe even some dignity and respect (especially since there is no dental or eye plan). Of course it will only be a matter of time before the hackers figure out how to code the software so that customers can still get their ya-yas off enjoying the perverse pleasure of arguing with a bot about the two-for-one yogurt deal.

I like to think that if everyone had to work at a Pottery Barn or Yankee Candle or Verizon store for just a few months we’d all be a lot nicer to one another. Miserable game recognizing miserable game, perhaps? It’s like bearing the mark of a secret society or fraternity. A nod, a wink, some sort of hand signal to let the other person know, “I see you. I’ll bus my own table.” Maybe that’s a stretch. But at one point no one thought it was possible to use pig parts to fix your heart. Miracles happen every day.

I held a handful of retail jobs through college and graduate school—The Disney Store, a Hallmark/gift type store, and eventually a Barnes and Noble. The products changed, customers did not.

The Disney Store was located in the mall in my hometown. It was a perfect job for my college schedule. I could work breaks and the occasional weekend when I was home. This was around 1995 and The Disney Store was considered a cut above conventional retail. Sorry not sorry, GAP. The company had outfitted and presented these stores as specialty boutiques. The concept was to extend the “magic” of the theme parks and animation franchise into a retail setting. Each store was meant to be experiential: big video screens playing Disney films; fixtures and decore that replicated the kind of design you’d find at Disney hotels and attractions. Some of the bigger, flagship stores were multi-story spaces able to host special events and promotions like character visits. Even our relatively small store had an outward facing “animation window” featuring an animatronic Sorcerer Mickey waving a wand. If you worked on Sunday and drew the short straw you’d have to squeeze yourself into a space the size of a middle-school locker to clean and dust.

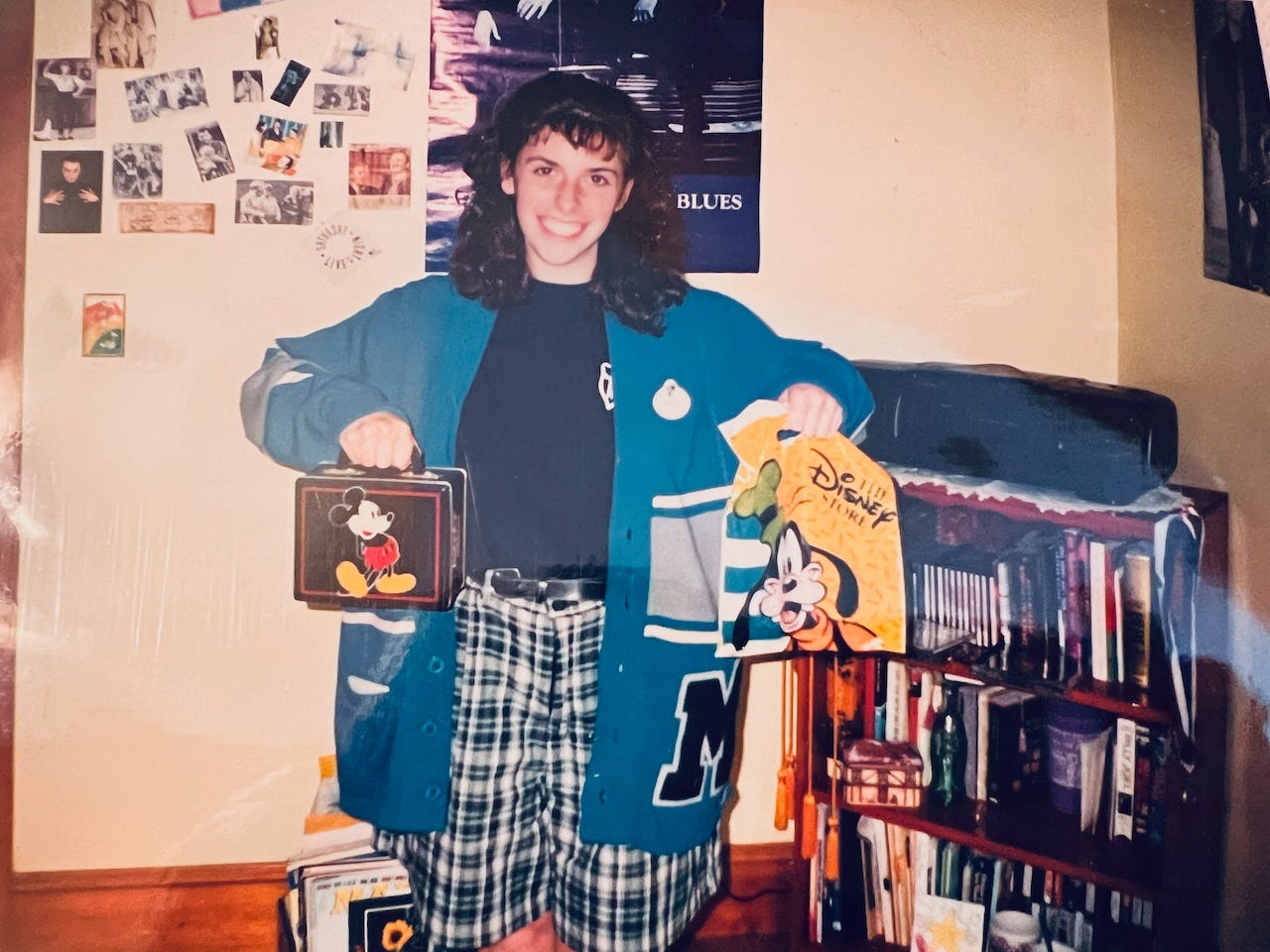

Working at The Disney Store felt kind of prestigious. Employees were referred to as “cast members” and given “costumes.” When I was hired they were still making women wear grey, pleated skirts and long blue and black lettermen sweaters like bobby soxers from the 1950s. Fortunately that trend moved into the more comfortable and dignified khaki pants, white shirt, generic cardigan costuming phase. Everyone I worked with took an enormous amount of pride in being employed by Disney, and I was right there with them. I grew up swallowing a fair amount of Disney magic. At the time, they were the gold standard of animated films as well as a certain kind of fantasy experience that was either simply unavailable anywhere else or done so poorly you wouldn’t be caught dead bragging about your summer at something called Boppo’s Adventure Kingdom Land.

Besides, we sold high-quality items that, pre-Internet, you could only get in one of our stores or the parks. Pricy, first edition animation cells hung on the walls behind the cash wrap; expensive watches, jewelry, snow globes, and other collectibles stood in gleaming glass cases; plush toys, clothes, and media were all shelved bearing the Disney stamp of superiority. All of this meant that we conducted ourselves with a certain amount of gravitas, class, and graciousness. The customers or, GUESTS, as we were required to refer to them, did not necessarily share in this same spirit.

People would change their kid’s diaper on the floor behind what we called Plush Mountain, a gigantic, pyramidal display of all the different types of stuffed creatures from the tiniest Donald to toddler-sized Mickeys. The soft, stinky evidence wedged into a corner of the mountain for someone to find. A few times we got people trying to “return” a product that wasn’t even Disney. We would watch them become more and more belligerent as they tried to convince us that they bought these Fivel Goes West pajamas, here, for a birthday gift just last week!

They stole, of course. Contraband walked out of the store tucked underneath blankets in the back of a stroller. Someone might carefully remove a clothing tag at the back of the store and then bring it to the cash wrap explaining it was a gift, no receipt. It was typically this type of thing. But the most spectacular feat of thievery occurred right out in the open on a sluggish Saturday afternoon.

The store wasn’t even that crowded, which was unusual for a weekend day. I spent most of my shift roaming around folding shirts and scooping plush Goofys and Simbas off the floor where kids had tossed them after hearing for the tenth time, “NO. We are NOT getting anymore stuffed animals!” I didn’t mind these kinds of shifts. You could almost put yourself into a pleasant meditative state performing menial tasks without having to actually interact with anyone. I was in that sweet mental spot when out of the corner of my eye I saw my manager, Helga, fly out from behind the cash wrap counter. She cornered so hard I thought she was going to take a hunk of plexiglass in the rib.

A man and a woman had grabbed three leather jackets and were making a break for it. The jackets were bomber-style, brown, weathered leather with hand-embroidery of Mickey and the gang riding in a bi-plane. The jackets sold for about $250 each, the most expensive item of clothing in the store. We maybe sold one a year.

There was no finesse to this steal. The couple saw a slim opening in the atmosphere of the store, hugged what they could to their chests, and ran. They didn’t factor in Helga racing after them like a hound on the heels of a rabbit. Everyone in the store froze. The assistant manager yelled for Helga to stop as she picked up the phone to call security. Whether or not Helga heard we had no idea. I think she must have, but didn’t care. Helga was a strong, take-no-mess type of woman in her thirties, a mother of two. If you were slacking off or goofing around with other cast members during your shift, she wouldn’t reprimand you immediately the way some of the other managers did—real Principal Skinner style. But she’d only extend that courtesy so far before telling you to cut the crap. Helga had made her career in retail. She had seen it all and survived even more. Retail forged Helga. This moment was her Alamo. Helga disappeared out of the store, nothing but a cartoon contrail sprinting through the mall after the thieves.

Later we found out that she pursued them the length of the first floor, up the stairs, all the way through the food court, and was nearly on top of them in the staircase leading out to the exit in the back parking lot of the mall when security caught up to everyone. Helga was gone for a few more hours giving the police her statement and then dealing with the tedious series of phone calls to corporate. Walt Disney himself could have spontaneously reanimated and walked into the store and the rest of us would have hardly noticed, still awestruck by what we had just witnessed.

When Helga returned to finish out her shift we clustered around her like groupies.

“That was dangerous,” said Kathy, a fellow cast member who had also been on the floor when the ordeal went down.

“They could have had guns or knives,” said Ken, who had barely started his shift when it all started. “You were lucky.”

Helga shook her head and shrugged. She stood by the cash wrap, hands on hips, looking around the store like a sheriff surveying the saloon, ready for whatever might shake down; just another day on the job in retail.

Lens Zen!

Welcome to the 117th day of January. I was lucky enough to catch a brief burst of color in the morning sky the other day, which I am cameling up to get me through the remaining 674 days of winter in New England. To all of those deep in the January funk—I see you. I salute you from beneath my blanket heap. Send hot cocoa reserves please.

My hit was everyone should have to work as a server in a restaurant so they forever knew what an adequate attitude and gratuity to the servers would be.

Just now getting to this post, but it made me laugh. In terms of monotonous jobs, I cringe with pity every time I take an Amazon return into my local UPS store. I wonder when the employees realized their jobs in shipping were turning into an unending series of 20 second interactions on behalf of ANOTHER COMPANY and what they think of it.